Dr. Gorge Palada, Romanian-Born Nobel Winner, Obituary, October 10, 2008 (NYT)

By ANDREW POLLACK

New York Times, October 9, 2008

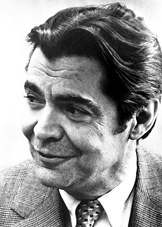

LOS ANGELES — George E. Palade, whose discoveries about the intricate inner workings of cells helped give birth to the field of modern cell biology and earned him a Nobel Prize, died Tuesday at his home in Del Mar, Calif., at 95. The cause was complications of Parkinson’s disease, said his wife, Marilyn Farquhar.

Beginning in the 1940s, Dr. Palade (pronounced pah-LAH-dee) pioneered in using electron microscopy and other techniques to discover tiny structures within cells and to discern their functions. He discovered the ribosome, the cell’s protein-making factory, and helped explain the way proteins are transported out of the cell, as when a pancreatic cell secretes insulin, for example.

Such discoveries later proved useful in understanding diseases and in the protein production that is the basis of the biotechnology industry.

“In cell biology he is clearly the most influential scientist ever,” Günter Blobel, a professor at Rockefeller University, said Wednesday. Dr. Blobel, who was once a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Palade’s laboratory, won a Nobel Prize of his own in 1999 for essentially following up on some of Dr. Palade’s discoveries.

Dr. Palade shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1974 with Albert Claude and Christian de Duve. Awarding the prize, the Karolinska Institute said the three had been “largely responsible for the creation of modern cell biology.”

In his acceptance speech, Dr. Palade said the new discoveries would lead to better understanding of diseases, many of which are caused by cellular dysfunction.

“Cell biology,” he said, “finally makes possible a century-old dream: that of analysis of diseases at the cellular level, the first step toward their final control.”

George Emil Palade was born on Nov. 19, 1912, in Iasi, Romania. His father, a professor of philosophy, had hoped the son would follow in his footsteps. But young George “preferred to deal with tangibles and specifics,” he would recall in the autobiography he wrote upon becoming a Nobel laureate.

He earned a medical degree from the University of Bucharest, but his interest was in basic science. So he went to New York University in 1946 for further studies and moved the next year to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, now Rockefeller University, where a new field was being born.

Scientists had started examining cells using light microscopes in the 19th century. But those microscopes were not powerful enough to see structures much smaller than the cell nucleus, so the field of cell biology had stagnated.

At Rockefeller, however, Dr. Claude had begun using a more powerful tool, the recently invented electron microscope. This was not a straightforward process, because the cells could be damaged as a result of it. But Dr. Palade helped refine electron microscopy of cells “to the highest degree of artistry,” the presenter of his Nobel Prize said.

He also helped develop a technique called cell fractionation, in which cells are broken apart and components are separated based on their density, using a centrifuge. This isolated each of the components so they could be studied.

In 1973, Dr. Palade moved to Yale, where he became the chairman of the new department of cell biology. In 1990, at 77, he became the first dean for scientific affairs at the School of Medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He retired in 2001. The school named a building for him in 2004, and a professorship was endowed in his name in 2006.

Dr. Palade won many awards other than the Nobel, including the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award and the National Medal of Science. As the only Nobel laureate from Romania, he was well known and honored in that country.

Those who knew him say he gave eloquent lectures and had a knack for clearly summarizing complex information. He had a vast knowledge of art, history, music and literature — “an old-fashioned European gentleman,” said Gordon Gill, the current science dean at the San Diego medical school.

Dr. Palade also trained legions of scientists. When the medical school had a symposium in honor of his 85th birthday, people came from all over the world, Dr. Gill said.

One of Dr. Palade’s postdoctoral researchers, Dr. Farquhar, became his wife in 1970. The two maintained independent laboratories and scientific careers, though they sometimes collaborated. Dr. Farquhar is now chairwoman of the department of cellular and molecular medicine at the medical school.

In addition to his wife, Dr. Palade is survived by two children from an earlier marriage, Georgia Van Dusen of Manhattan and Philip Palade, a professor of pharmacology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock; two stepchildren, Douglas Farquhar and Bruce Farquhar, both of San Diego; and two granddaughters.